by Alan Jordan

The knee is the largest and most elaborate joint in the human body. It consists of two articulations, one between the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) and the other between the femur and patella (knee cap); and they are both very prone to injury.

In this article, we’re discussing a particularly severe injury, which requires lengthy rehabilitation. Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) compromises knee stability and management varies depending on the patient’s sporting activities, lifestyle, age and co-morbidities.

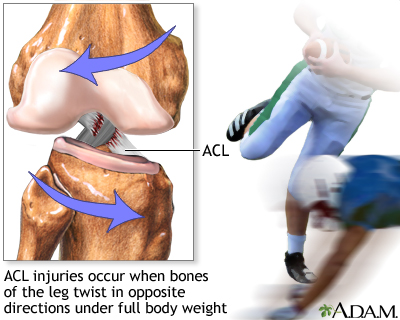

Picture courtesy of MedlinePlus.

Anatomy & Function

Briefly and simply, the ACL attaches from the femur to the tibia in an oblique angle. It comprises of two bundles of collagen fibres, which control anterior translation and medial (inward) rotation of the tibia over the femur. These provide about 85% of the knee stability. The remainder is dependent on muscle bulk and tone. Quadriceps, hamstrings, adductor muscles (inner thigh) and muscles inserting into the Iliotibial band – Tensor Fascia Lata & Gluteus medius. This is why non-traumatic injuries of ACL are more common when fatigue of these muscles kicks in.

Mechanisms of Injury

There is a higher prevalence of ACL injuries amongst females with a ratio to 3:1. Both internal and external risk factors have been studied, such as hormonal, anatomical, footwear, environmental and neuromuscular (NCBI) factors.

Non-traumatic injuries to the ACL usually occur as a result of a quick deceleration, hyperextension or rotational injury. Such injury often occurs following a sudden change of direction with the patient typically reporting that they felt a popping sensation in the knee.

Traumatic injuries usually happen when hit from the side. Injuries to the ACL are often associated with medial meniscus and medial collateral ligament (MCL) tears, collectively known as the “unhappy triad.” In adolescents, the ACL may avulse from the tibial spine instead of rupturing.

Clinical Presentation

This depends on how quickly the patient gets to the clinic. Examination may take place at the pitch-side if a health practitioner is available. Immediate examination might be hindered by pain and certain tests would not be possible. On the other hand, presence of laxity may be easier to examine before swelling develops. Seeing a patient 2-3 days post injury sometimes makes it difficult to get a clear idea of the extent of damage because of the limitations caused by swelling and pain.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can be very useful in cases where an immediate diagnosis is required. This also helps to identify associated injuries, such as damage to the medial meniscus and MCL. In patients who come to visit the clinician a few weeks post injury, clinical examination can give a good idea of the extent of damage with special orthopedic tests.

Non-Surgical Management

- Mobility

- Swelling

- Range of movement

- Pain management

- Muscle inhibition/retraining

The immediate management would be controlling the amount of swelling/inflammation and pain. Medication, ice, compression and elevation are very important initially. The patient is taught how to use crutches and instructed to gradually mobilise the knee in a non-weight bearing manner. Muscles tend to ‘switch off’ with such an injury and wastage happens very quickly.

In the meantime, the patient has to decide whether or not to undergo surgery. This decision should be based on personal preference, age, level of activity, extent of damage, and knowledge of the possible consequences if the knee is left unstable and excessively loaded.

In the case of non-surgical management, the patient is encouraged to strengthen muscle groups, such as quadriceps, calf muscles and very importantly, hamstrings. Proprioceptive control (balance, joint awareness) is also very important.

Surgical Management

In the case of surgical management of ACL rupture, the patient and orthopedic consultant discuss the graft to be used. The most common options would be grafts cultured from hamstring tendon, patellar tendon or a donor graft.

Different surgeons have slightly different approaches to the post-operative approach. Although rehabilitation must be personalized according to the patient’s recovery rate and level of activity required, it is important that the physiotherapist and surgical team work together in providing a coherent program.

The author Andre Bason is the Director of Physiotherapy at Broadgate Spine and Joint Clinic. For more information go to https://www.broadgatespinecentre.co.uk/london-physiotherapy/.